A fatal flaw that businesses make is taking raw data and information and overwhelming their audience with facts and figures. They don’t understand that we need to engage with customers using emotion, influence their thinking with story, and only then can we persuade them accept our philosophy.

There is one brand, throughout history, that achieved the marvelous feat of turning information into stories and insights better than everyone else. The name of that brand is Leonardo Da Vinci, the 16th century polymath. If you’re confused and you can’t believe that a person can be a brand, then you only need to look at Oprah, Walt Disney, Michael Jordan, and many others who have turned their name and persona into a global brand that generates billions of dollars.

The Last Leonardo: Salvator Mundi

The brand that is Leonardo da Vinci is even stronger. In 2005, a painting entitled Salvator Mundisold for less than $10,000. That was before experts realized who the painter was. Once it was confirmed that the painting had been done by Leonardo’s brush, Salvator Mundi sold again at Christie’s Auction House for a mind-bending $450,300,000.

That’s a remarkable, unfathomable markup of 4,503,000%. There is no brand, existing today or in the past, that can command that kind of a markup or margin for brand association. And we haven’t even discussed his most well-known painting, the Mona Lisa.

I would be surprised, even appalled, if that painting ever went on auction for less than $5 billion. Just imagine all the billionaires lining up and competing for the right to say they own the painting of Leonardo da Vinci, that was owned by the King of France, Francis I, and hung in the bedroom of Napoleon Bonaparte, the world’s most famous general who conquered Europe and become emperor.

The Scientist Who Liked to Paint

But what do Leonardo’s paintings have to do with storytelling? Well, what many people don’t know is that Leonardo wasn’t just a painter; he was and wasn’t—he was more.

You see, when Leonardo was 30 years old, he sought to be employed by the Duke of Milan. And in his eleven-paragraph resume, Leonardo defined who he truly was. He used the first ten paragraphs to describe his scientific and engineering skills, his ability to design bridges and waterways for transportation, cannons and armored vehicles for warfare, and buildings and roads for city planning. Only in the eleventh paragraph, all the way at the end, did Leonardo add, “Likewise in painting, I can do everything possible.” That was true—he had no equal.

He would go on to create the two most famous paintings in history, The Last Supper and, of course, the Mona Lisa. But in his own mind, he was a man of science and engineering and a master at conveying the discoveries from his thousands of pages of detailed notes through painting. It was his method of turning data into stories and learning into beauty. He was a scientist who used art to deliver his discoveries.

Stories Should Communicate Truth

When people hear the term “story” in a business setting today, or the term “business storytelling”, they immediately assume it’s somehow in conflict with truth and authenticity. That’s because stories most often lead with introductory words that tell us to forget facts (Once upon a time…) and they beseech us to embrace inaccuracy (…in a land faraway).

Things weren’t always this way. The editor of a major daily newspaper, say the Washington Post in 1970, could ask investigative reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, “So, what’s the story?” as they returned from an assignment to uncover the Watergate scandal.

“What’s the story?” wasn’t an invitation to tell a tale, misinterpret real events, or turn reality into fiction. It simply meant, “What have you learned? What’s the latest news? What’s the scoop?”

In truth, business storytelling relies on facts, numbers, and careful analyses. When you add to it a narrative, strong emotions, and guidance about what happens next, that’s when you have a story. It’s certainly one powerful way of shaping a business.

Epitome of Weaving Data and Creativity: Mona Lisa

Master Leonardo was an expert storyteller. He pursued art to satisfy his need to tell the truth about anatomy, the heart, optics, mathematics, and more.

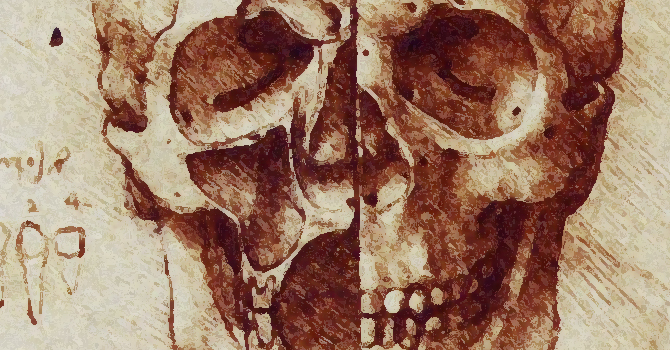

He sawed off human skulls to study how teeth were set in the jaw. Then he peeled the skin from cadavers to study the muscles. His dissections led to diagrams, which led to charts, charts led to sketches, which led to beautiful drawings, which were then translated onto canvas.

He was particularly fascinated by human lips. “The muscles which move the lips,” he wrote in his notebook, “are more numerous in man than in any other animal.” Leonardo was the first man ever to dissect with his own hands the face of a human to see how the muscles that move the lips also raise the nostrils of the nose. He wrote about it extensively in his notebooks:

“The muscle shortening the lips is the same muscle forming the lower lip itself. Other muscles are those which bring the lips to a point, others which spread them, others which curl them back, others which straighten them out, others which twist them transversely, and others which return them to their first position.”

At the time, Master Leonardo was working on the Mona Lisa. And instead of publishing his research about the human mouth, teeth, lips, and nose in a textbook like so many have done, he painted the most beautiful and recognized smile in the world.

He took someone ordinary, not an aristocrat or wife of a wealthy merchant, and made her the most famous woman in history. Definitely the most famous smile.

This was his way. He knew what most businesses today have yet to figure out. That is, consumers don’t care about data—on its own data is nothing. The insights you glean and stories you tell from the data is everything!

That’s because stories are about people and feelings and consumers base their decisions on feelings rather than well-formed thoughts and opinions. They enable us to identify with and care about people who we never met, who lived in a completely different time, and a totally different place.

A Life-and-Death Story

On May 22, 1948, Ralph Edwards, the host of the radio show Truth or Consequence, interrupted his usual broadcast to bring people a life-and-death story.

“Tonight, we take you to a little fellow named Jimmy.”

“We are not going to give you his last name,” Edwards explained, “because he’s just like thousands of other young fellows and girls in private homes and hospitals all over the country. Jimmy is suffering from cancer. He’s a swell little guy, and although he cannot figure out why he isn’t out with the other kids, he does love his baseball and follows every move of his favorite team, the Boston Braves.”

“Now, by the magic of radio, we’re going to span the breadth of the United States and take you right up to the bedside of Jimmy, in one of America’s great cities, Boston, Massachusetts, and into one of America’s great hospitals, the Children’s Hospital in Boston… Give us Jimmy please.”

Then, across the entire nation, Jimmy could be heard.

Jimmy: Hi.

Edwards: Hi, Jimmy! This is Ralph Edwards of the Truth or Consequences radio program. I’ve heard you like baseball. Is that right?

Jimmy: Yeah, it’s my favorite sport.

Edwards: It’s your favorite sport! Who do you think is going to win the pennant this year?

Jimmy: The Boston Braves, I hope.

Edwards: Have you ever met Phil Masi?

Jimmy: No.

Phil Masi (walking in): Hi, Jimmy. My name is Phil Masi.

Over the static, the audience could hear Jimmy’s gasp.

Edwards: What? Who’s that Jimmy?

Jimmy: Phil Masi!

Edwards: And where is he?

Jimmy: In my room!

Edwards: Well, what do you know? Right here in your hospital room—Phil Masi from Berlin, Illinois! Who’s the best home-run hitter on the team, Jimmy?

Jimmy: Jeff Heath.

(Heath entered Jimmy’s hospital room.)

Edwards: Who’s that, Jimmy?

Jimmy: Jeff . . . Heath.

One by one, player after player, the Braves entered Jimmy’s hospital room bringing T-shirts, signed baseballs, game tickets, and caps.

At the end of the broadcast, Edwards lowered his voice, “Now listen, folks. Now we know that one thing little Jimmy wants most is a television set to watch the baseball games as well as hear them.”

“Let’s make Jimmy and thousands of boys and girls who are suffering from cancer happy by aiding the research to help find a cure for cancer in children. If you and your friends send in your quarters, dollars, and tens of dollars tonight to Jimmy for the Children’s Cancer Research Fund, and over two hundred thousand dollars is contributed to this worthy cause, we’ll see to it that Jimmy gets his television set.”

The public response to Jimmy’s story was staggering. Even before the Braves had a chance to leave Jimmy’s room that night, donors had lined up outside of the lobby at the Children’s Hospital.

Others mailed dollar bills, wrote checks, children mailed in pocket change, and in a few days, more than $231,000 poured in.

Jimmy received his television set. A new building with all the bells and whistles was established. New steps, graded by only an inch were designed, so that children could easily climb them. Waiting rooms had boxes full of toys. And a library full of books and hallways painted with storybook characters were commissioned.

Jimmy’s story had captured the heart of the nation.

When you take truth, facts, data and communicate them through stories that combine an idea with an emotion, you get astonishing results.

Leonardo’s ability to take truth and paint it with a story led him to serve wealthy merchants, Dukes, warlords, one Pope, and ultimately, led him to join the court of Francis I, the King of France. That was the master storyteller Leonardo da Vinci. The likes of which has never been matched, not even by Michelangelo.

The world is full of artists, but there is only one super artist.

0 Comments